Sean Whittle

In a previous blog I told how my Dad inspired me to begin Lumiere Charity. On many occasions when I was on holiday, I used to go with Dad and help him, my brother Joseph and our dear friend Elsie to give out soup, bread, food and comfort to those who otherwise would have been starving in many areas of the mining towns, townships and rural villages in Free State, South Africa. For 17 years he sacrificed all to feed the poor. Dad went peacefully to his eternal reward in 2008. My mom Luky Whittle wrote the following about him, reflecting on Dad who was known as extraordinary Father to the Poor.

Not long ago, in the mining town of Virginia, Free State, a stone was laid on the grave of my late husband Seán Joseph Whittle (pictured). It holds a statue of the Sacred Heart, about a metre tall, and a dedication. Whenever I look at the simple inscription, so fitting to grace the grave of so humble a person, I remember Seán, the man whose industry, sweetness, brilliance of intellect, charm and humour for half a century brought a deeper dimension to my life than I might otherwise have known.

We shared tragedy together after the birth of Joseph, our third child, who sustained brain damage during a most complicated confinement. Rather than dividing us, this shared pain drew us closer together.

Although two such different characters as Seán and I were bound to clash, I learned from his quiet example. While he seldom reprimanded me for my verbal excesses, I learned to emulate his silent example of respect for others.

I like to think that I taught him something from my side. As a miner, he earned good money and received excellent fringe benefits. However, as one penniless immigrant who had married another, he experienced what I considered to be an almost obsessive need for security, insisting that charity should start at home. For my part, I believed everyone should share in our good fortune. Sometimes there was friction between us on that account.

I think I convinced him of my point of view the day I explained that the price of a 25kg bag of special nutritional soup powder, fortified with vitamins and minerals, enough to feed hundreds, is equivalent to that of a bottle of whiskey. A massive bag of maize meal costs less than some CDs do. Seen in this way, charity comes cheap at the price.

When he became a pensioner, I was pleasantly surprised when he founded a soup kitchen, which he ran for 17 years. He used the money he had saved to meet the calls on the soup kitchen bank account. Welkom, where we lived, had its full quota of unemployed miners. He kept thousands of them fed until they found jobs. He was dearly loved by his needy clients. Driving besides him in town, I felt I was sitting next to Nelson Mandela. Everyone smiled and waved.

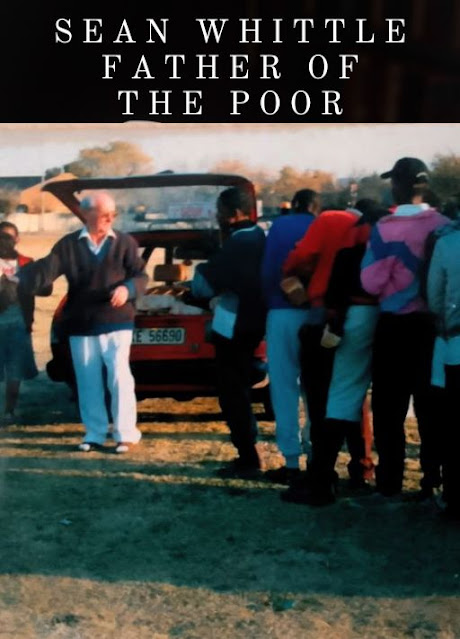

Seán Whittle distributing food

Assisted by our Joseph, he rose at five in the morning to cook the food he had put ready the previous evening in massive pots on six primus stoves in the garage before transporting it to various venues in towns and townships in his ancient red car. He collected bread, which had reached its sell-by date from a local bread factory, to the chagrin of some pig farmers who had previously collected this bounty and felt he was trespassing on their territory. Queues of up to 300 people were served daily. A fellow parishioner, a mechanic, kept his ancient Mazda roadworthy, never charging him for labour and sometimes even secretly supplying some of the spares free.

When his generosity became so blatant that Seán felt bound to challenge him, he countered: “Do you think you’re the only person who wants to go to heaven?”

It amazed me that for 17 years, our unproductive (humanly speaking) son Joe with his mental age of five kept thousands of people fed by his hard work and sheer physical strength. By the time Seán ran out of his own money, people were giving him donations which kept the streams of soup flowing. Whenever during the month the donations ran out, he filled up the gaps from his pension and my salary. It was a source of never-diminishing wonder to me that everyone always got something to eat and that our own family survived as well. When I got too ill to work for a while we thought we’d have to close the charity down, but a benefactor contributed a monthly cheque equivalent to my salary until Seán had a stroke and his work ended.

For his service to the community, Seán received the Melvin Jones award from Lions International and the Paul Harris award from the Rotarians. People sometimes told me he was a saint but I didn’t experience him as such for his osteo-arthritis coupled with his incredibly hard work sometimes caused him to be brusque, impatient and withdrawn.

I never felt overawed at the incredible effort he put into the running of his charity, rather experiencing it as keeping a nice sense of balance between his human frailty and his generosity. I grew resentful when I felt the work was playing havoc with our social lives and our family life. Yet, watching him at his work and seeing the mountains of food prepared in our humble garage by only two pairs of hands, I felt in awe, like the Hebrews who watched Moses go up to the mountain to meet God. If that sounds contradictory I can’t help it. That’s how it was.

Only once did I object. He had sold a flat we owned jointly with the bank and after settling with the latter we used the money to pay off the soup kitchen overdraft. Less than a week later he wanted to borrow a further R500. After a week of financial stability I had got used to sleeping well at night. I told him I would not let the soup kitchens take us down, “Charity begins at home, remember?” Shocked, he said he couldn’t believe it was I talking. “Believe it!” I said. “If Our Lord wants you to run the soup kitchens; he has to see to it that the money is provided. If you and I end up bankrupt, we won’t be able to help ourselves; much less others.”

Then I left home for a church function where one of our priests gave me R500 for the soup kitchens. Less than an hour after my refusal I arrived back at home, triumphantly waving the notes in the air. Seán broke down and wept. After that he never again spoke about finance for the soup kitchens with me and I asked no questions about money. Ignorance is bliss.

I asked him one morning if he wasn’t scared of being killed in the townships where he moved so freely despite the political violence. Though he generally answered one question with another, this time he gave me a straight answer. “I’m always scared, but even if I knew I was going to be killed today, I would still go and feed the poor.” That day my regard and respect for him reached their summit.

“When you die and get to heaven, a shout will go up to welcome you,” I said warmly. A deeply humble man, he was horrified, “Please, please! Don’t say that! It’s wrong! I’m a dreadful sinner!” “Another thing,” I continued, ignoring his protests, “when you die, I’ll put a stone up on your grave which will read: ‘He was a Father to the Poor’.” He didn’t argue further but burst into tears and went out.

A lot of water had run under the bridge since that day. Seán had continued to feed the poor until he sustained the stroke, which forced him to take to bed where he remained until his death three and a half years later.

Joseph tended him lovingly as he uncomplainingly suffered the agonising pangs of osteo-arthritis, becoming almost paralysed in the end. The charity continued in other ways when others initiated similar projects. Seán had shown them that it is possible to serve the poor on a shoestring.

He became ever more quiet and one day he said: “When we open our eyes in death…” In the end he sometimes became muddled in his speech and reactions. Yet he remained sane. The Sunday before he died, he said: “Please tell that man sitting beside my pillow to get off and go away.” “Why? Is it an ugly man?” I asked. “No! It is a very beautiful man. But I don’t want God to come and fetch me yet.” “Why hold back if it is your time?” “Because I want to suffer for the remission of sin.”

The day he opened his eyes in death seemed to me to be a day like any other. I came home from my teaching job. In the morning I had told him my students were battling with a project and asked him to offer up his sufferings of the day for the success of the assignment.

“How did the students fare?” he asked. I cooked, and Joseph fed him. Then our widowed daughter Jacinta at whose house we stayed helped Joe and me to clean him up and change the bed linen. Our two granddaughters joined us and we were sitting on the bed, laughing and talking, when Seán said, “I’m concerned about the fact that you and Jacinta are so free with your money.”

When I explained that we were learning to be frugal and managing to keep our heads above water he visibly relaxed. Suddenly the eyes of Jacinta, a nurse, narrowed. “Daddy, are you battling to breathe?” “How can you tell?”

I telephoned a doctor who instructed me to bring him to the hospital immediately. As we tried to lift him into his wheelchair, he stiffened. He had always been terrified of death. I had my arms around him and melted with compassion for him. I heard myself say: “Look at you having a panic attack. When you were born, God did not need your help. When you lived for 75 years, he kept you alive without your assistance. Whatever is happening to you now, just surrender. God still doesn’t need your help.” At that point the tension left his body. He relaxed and died with his beautiful head against my shoulder.

That was on August 26, 2008. A year later we erected a stone on his grave. As I had promised him the day he cried so much, it reads: “He was a Father to the Poor.”

* Blog post with kind permission from Dr. Luky Whittle

No comments:

Post a Comment