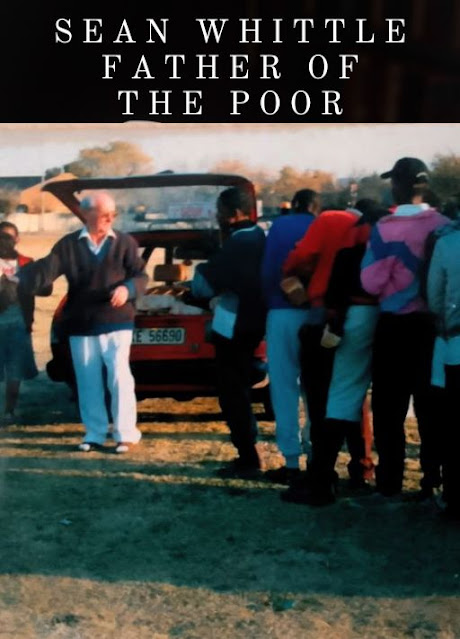

It was four am in the dark South African morning, and Dad was well on the go with his Charity rounds. He had invited me to go along with him as it was 'a special visit'. I was intrigued, and when Dad mentioned something special with that Irish twinkle in his eye, it always promised to be an interesting time. We bowled along the dusty township road in the creaking old red Mazda that at times seemed to be held together with some pieces of twine and a prayer, and the tyres shook over a rutted village road as we went further and further into the shack areas. Overhead the one white star sparkled brightly, the Free State wind blew with the balmy scent of South African foliage, and I couldn't have been happier. The little dog Norman, a feisty and loveable black-and-brown daschhund, perched with his legs up against the seat and his ears flapping in the breeze from the window.

Eventually we stopped outside a little shack. A stately elderly lady sat fully dressed in the doorway, her feet encased in slippers and her two hands clasped on a small

knobkerrie, a walking stick. She had a scarf tied neatly around her head, and her whole stature was one of eager expectancy. Dad whispered to me, 'This lady is blind, and unable to get to town for her pension. I bring her food every day, and blankets and shoes when she needs them. I also bring food for the family. Stay here and talk to her, while I visit the family'. And Dad, with his impeccable Irish Tramore courtesy, knocked at the corrugated iron door of the main shanty and whipped off his old

veldt* hat as the lady of the house answered the door with as much courtesy as if he were meeting royalty.

I spoke to the old lady, '

Dumela, Mme,' and went through the Sotho form of greeting courtesies as my beloved South Sotho friends had taught me in my youth. Mme Maureen* courteously asked me when the Father was coming. I explained that the Father was my dad, and he would be coming shortly after visiting her family. She bent over her walking stick, and fixed me with her unwavering sightless gaze. 'You do know what the Father does for me, don't you?' she asked. 'He looks after my family with food, pap, clothes, blankets, oil and candles so they don't need to use my pension anymore. Before we were so poor, that the pension I got was all we had to live on. Then

Modimo (God) sent the Father, and he took care of my family. Because of him, my grandchildren are now going to school, and have shoes to wear. Now the Father organises for me to go to the pensions office with my daughter, he takes the two of us together so we can draw my pension. Then the Father takes me to the doctor, so that I can get the medicine I need to keep me well. Now I am much better, before I was on blankets on the floor, and could not walk. Now I can walk, and I have a bed. A proper bed. You are very blessed, little one, to have such a father. He truly is a great man.'

And I watched as Dad came out of the shack, followed respectfully by three little children, two boys and a girl, all dressed and ready for school, and their mother who was giving them instructions as to how to behave for the day at school. We all climbed into the car, with the matriarch in the front seat and Norman sitting quietly in the back of the car on his best behaviour. As we made our way into the nearest town, the exquisite South African dawn broke through the baobab trees on the veldt with gold, red and tawny rays. Once the children had excitedly run off to school, Mme Maureen and her daughter went in for the pension, and then we drove on to the doctor. Once all had been organised, and the two ladies dropped off at home, it was time to get to the first soup kitchen, where Dad organised food for the homeless, street children, prisoners just released from prison and unemployed. I couldn't believe the range of his good works, done in the name of the Lord.

And now, many years later, I still can't get over the last words of Mme Maureen. She said, 'Yes, I always look forward to a visit from the Father. But mostly, because he always spends time to talk to me, and asks me about my life. Before the Father came, I used to be so lonely. I used to sit in my room, and have no-one to talk to. My daughter was so busy. But the Father explained to her and my family that it is important I have someone to talk to. And now people visit me all the time.

The Father, he brought me happiness and an end to my loneliness. Before I was blind and I could not see anything at all. Now I see with the eyes of my heart, because the Father has taught me to feel happy and useful again. I told the Father I was of no use anymore, and he made me see that I am so important to my family because I have the time to talk to the children and teach them the old ways of

ubuntu, of the importance of community and caring. I am important because I have brought them life and brought them up. But most of all, I am important because I am me, a special person.' And Mme Maureen beamed with pride. 'Yes, I am special. Because each of us is special.'

And I realised as Dad and I drove home after a very busy day at the Free State Soup Kitchens Charity, that the greatest gift Dad had brought to this family was an end to the loneliness Mme Maureen had suffered. In the spirit of Lumiere, please think of someone in your neighbourhood or area who is elderly, ill, or blind. Please extend your hand in friendship to them, and assist them in some way that they need. Another option is to visit a Retirement Home, there are many people who are elderly who sometimes have no-one to visit them. Perhaps Providence has ordained that you be the one inspired to bring happiness into their lives with a visit, assistance, flowers or card. As we go into this New Year, may God bless your and your families, and all those who are elderly and ailing that we - the larger human family - may link hands so that no-one may feel lonely, uncared for, or unwanted.

*veldt - felt

Dumela, Mme - good day, ma'am

Mme Maureen - name has been changed

* Photograph taken by Rev. Catherine of street art in Africa